Jensen Huang Says "Strategy is Storytelling" - But What Does That Mean?

It's a Nice Sound Bite. And It's Actually Literally True

Jensen Huang, said in a recent interview with Wired Magazine that “Strategy is storytelling.”

Nice soundbite. But what did he mean by that?

Before I try and take the proposition seriously, I might as well admit that he could have just needed something to say to the journalist. Good for you Jensen! Way to come up with alliteration on the fly.

But I tend to think the offhand statement came from somewhere deeper in his past experience and the reason he could trot it out so casually was because it was well-worn from frequent use.

If we pretend for the sake of argument that strategy really is storytelling, then where does that lead us? Because other than their shared “S,” Strategy and Storytelling don’t seem to have much in common.

A corporate strategy is, after all, a plan - a map from point A to point B. It takes inventory of the company’s resources, measures the inputs and outputs of current and future iterations of the business model, proposes new versions and and products to take advantage of new market opportunities. Strategy is a technical, mathematical, analytical endeavour aimed at quantifying the unquantifiable future and knowing the unknown with enough fidelity to make it real. If you’re building a strategy, then you’re engaged in picking out and making possible one particular scenario out of the myriad potential versions of tomorrow. You’re not just making stuff up.

Strategy building sounds much more serious and important than storytelling. It sounds like something you’d do in Excel not Word. In a way, strategy and storytelling seem like opposites. Strategy must be realistic, thorough, and empirical while storytelling (at least as we usually think of it) is limited only by imagination and creativity. You probably wouldn’t want your accountants getting creative with the books and you probably wouldn’t want your CEO getting creative with the strategy.

Or would you?

The Mission is the Boss

Another Jensenism is “The mission is boss.” This pithy statement fits our preconceived notions a bit better. If you happen to work with a few dozen or a few thousand smart, hardworking, analytical people, then it’s far more motivating and empowering for them to work for a mission than to work for a boss. A boss may have a few good ideas, but a mission requires your ideas. A boss may give you a list of to-dos, but a mission requires you to come up with your own lists. A boss requires you to punch a clock and do what you’re told, but a mission requires everything you’re capable of.

The thing is, a mission is just the ending chapter of a strategy. It describes the future as it will be one day, as we can make it if we each do our part. But if “our part” is strictly defined from the top down by a single person, then it not only stifles enthusiasm but also limits the scope of analysis. In this way, rigor and precision on the part of the leader in dictating the details of a strategy actually limits the rigor and precision applied to the strategy as a whole.

Huh?

Let me explain.

No leader, no matter how prescient, could possibly describe a strategy in as much detail as the imagination of every one of her employees. For the same reason that the Soviet planners couldn’t accurately predict and direct supply and demand as well as the free market could, the CEO can’t predict and direct all the elements required for a strategy to succeed. In order to apply analytical rigor to every level of the strategy, she has to engage every member of her organization so that they are predicting and directing their own small (or large) part of the whole.

The problem, of course, is that if strategy is completely open-sourced to all of a company’s employees, then the result is likely to be full speed in all directions. Every employee is going to have a slightly different take on where the company should go and if the company tries to go all those places, it’s likely to stall.

The way to thread this needle between the need for focus and uniform direction and the need for individual creativity, analysis and engagement is to turn your strategy into a story.

A Mental Model - That Grows With the Telling

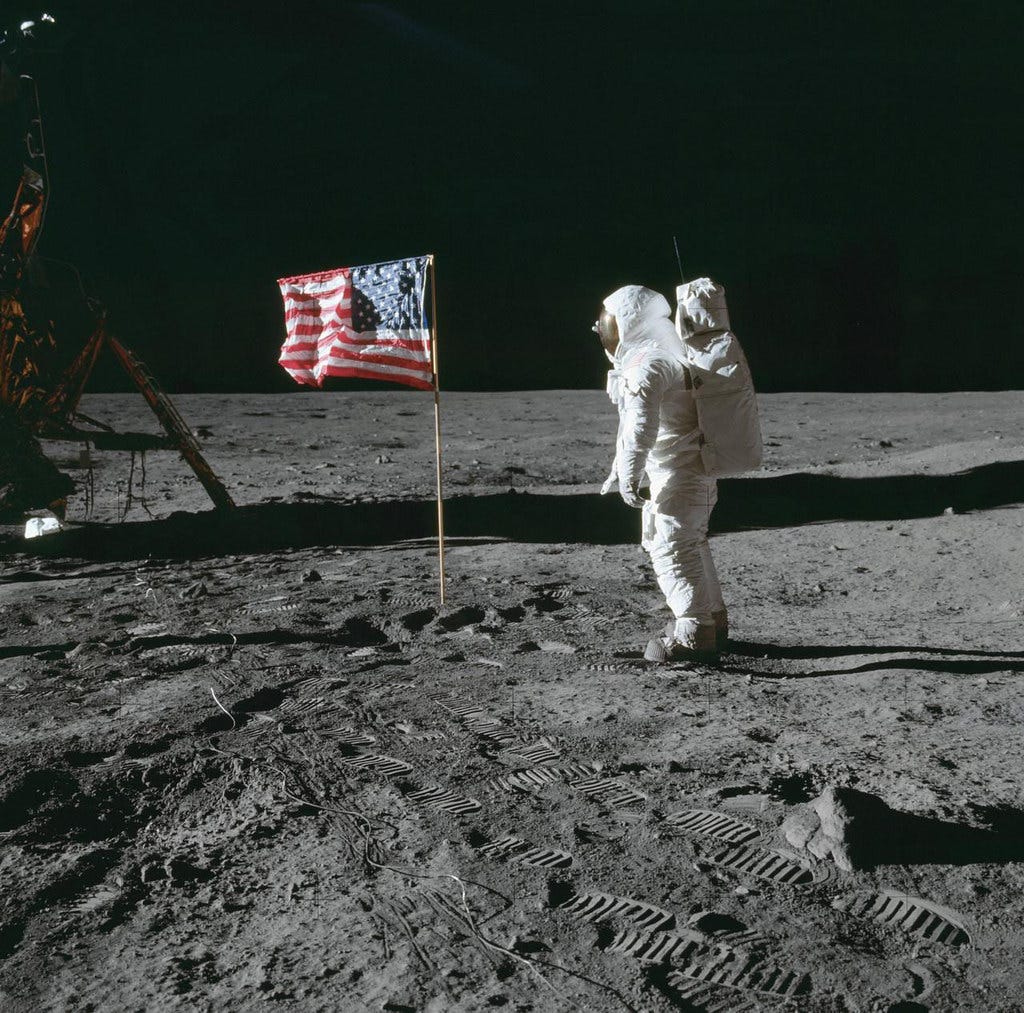

Because a story is an idea. And an idea is a mental model which is passed from mind to mind in a way that actually increases the fidelity and nuance of the model. A handsome young president can tell a story about Americans going to the moon and how doing so will prevent world war and seven years later, the minds of thousands of people put to work through the medium of space and time can turn this small step into a giant leap.

Without a story, a strategy is just specifications. In his memoir “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!”, the Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman tells this story about working with a group of young engineers recruited to the Los Alamos project who were lagging behind:

The real trouble was that no one had ever told these fellows anything. They sent them up to Los Alamos. They put them in barracks. And they would tell them nothing.

[...] I said the that the first thing there has to be is that these technical guys know what we’re doing. Oppenheimer went and talked to security and got special permission so I could give a nice lecture about what we were doing, and they were all excited: ‘We’re fighting a war! We see what it is!’ They knew what the numbers meant. If the pressure came out higher, that meant there was more energy released, and so on and so on. Now they knew what they were doing.

Complete transformation! They began to invent ways of doing it better. They improved the scheme. They worked at night. They didn’t need supervising in the night; they didn’t need anything. They understood everything; they invented several of the programs we used.

[...] As a result, although it took them nine months to do three problems before, we did nine problems in three months, which is nearly ten times as fast.

The moon landing and the atomic bomb were arguably the two biggest and most ambitious engineering projects in human history. The strategy for both was a story. The story had details, of course. It wasn’t pure imagination. But the story was the unifying idea - the mental model - shared by thousands of people which deepened analytical rigor and motivated action.

Your Market Tells The Story

Even customers take part in the story - in propagating and enriching the idea. I remember clearly the feedback we gathered from Bloomberg in 2004. They thought our product was more secure than the competition’s even though our company was 1/100th the competition’s size. It hadn’t really occurred to us before that, but we retold the security story to ourselves, scoured the details of the market, and began to focus on how to make our product even more secure. With every retelling, the story got better and better until we were selling to The US Air Force, the Federal Reserve Bank, and American Express.

It is possible (like early in the Los Alamos project) to get people working on a strategy devoid of story - a strategy which is just specifications and “tell them nothing.” But unless and until the the strategy can be shaped as a story so that it passes from mind to mind in an ever-expanding network of interlaced details, it will remain inert and lifeless.

Strategy is storytelling because strategy must be shared across the minds of tens of thousands of people: employees, partners, investors, customers. Otherwise, there’s no way it can encompass all the myriad details it will encounter out in the wild. There’s no way a single person can create the specification for future success, but a single person can tell a story that grows deeper and more meaningful with every retelling.