Marketing Fast and Slow

What the Psychologist Daniel Kahneman Teaches Us About Positioning

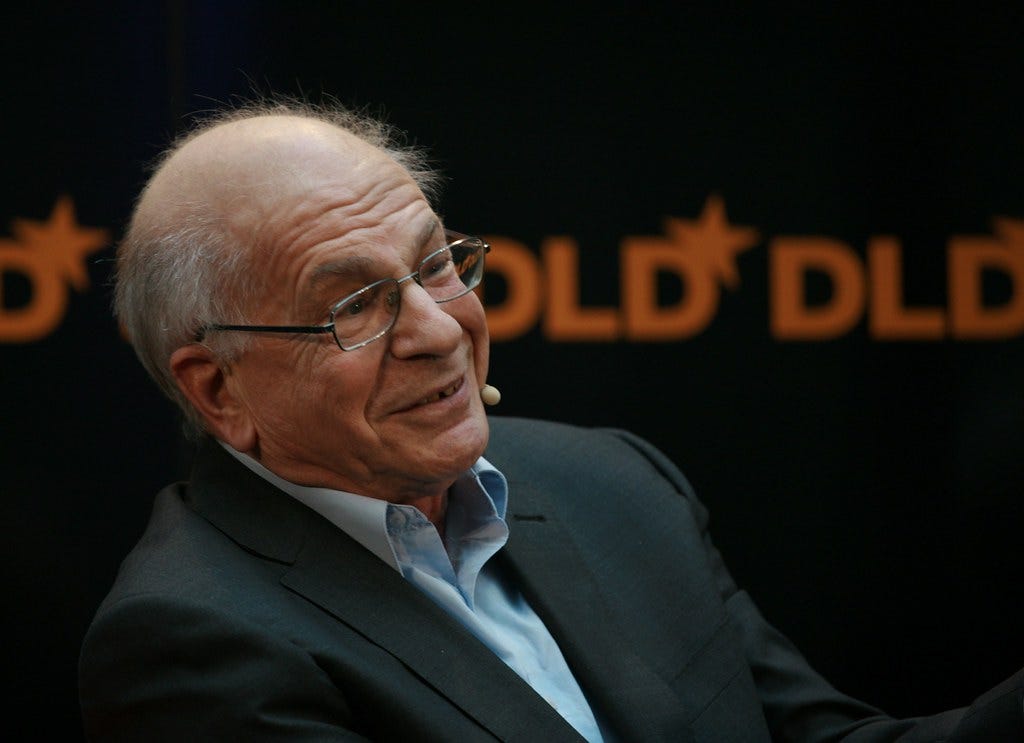

Daniel Kahneman passed away March 27th at the age of 90. He was a psychologist who received a Nobel prize in economics. His monumental work Thinking Fast and Slow has influenced my thinking on messaging and positioning as much as any other book except for a couple written by Al Ries (the godfather of positioning). This, even though the book is not about marketing.

Kahneman’s core insight is that our thinking - our psychology - is not one-dimensional. Human’s vacillate between two different modes of mental assessment depending on the nature of the problems we encounter. Sometimes we choose the right mode for the job and sometimes we don’t. Anyone who hopes to communicate complicated concepts effectively to their fellow humans has to work within the capabilities, predilections, and limitations of these two ways of thinking.

Here’s the model Kahneman lays out.

Thinking Fast

In most circumstances, we think fast. This is because we’re constantly scanning our situation with our eyes and our mind and our brain fires a billion neurons at once, allowing us to react with the speed of recognition to most challenges.

If you’re hurtling down a trail on your bike and a big dog jumps out of the bushes, your brain crunches all the numbers and tells you what to do. It tells you whether the dog is mean, it tells you whether you can stop in time or must swerve, and it also tells you whether you have room to maneuver. In these situations, we often find that our reactions pre-dated any conscious thought. Whatever decisions we made in the instant were made as much by our body as our mind.

If your wife walks in and notices the new widescreen TV you’re installing in the living room, you can tell in an instant whether she is pleased or irritated. You don’t have to wait for her to fill out a form, list her emotions, or calculate her level of agitation. You just recognize intuitively what her face and body are telling you and you prepare for fun, flight, or fight accordingly.

If you’re an expert in jiu jitsu or gymnastics, your brain tells you when your body is in the right position to execute the flip, throw, planche or pin. You don’t need time. You don’t need a committee. You don’t need a spreadsheet or a calculator to tell you these things. You just know, and you know in an instant.

And Slow

On the other hand, if I ask you to calculate 485 x 382 in your head, then you flip into a different type of thinking entirely. You don’t recognize the answer like you recognize an old friend. You must deliberately analyze the question and deliberately calculate the answer. It’s a slow, laborious process. It takes you out of the moment; it narrows your intake of new perceptions until you have determined the solution to the problem.

We encounter many problems solvable by intuitive thinking, but also a fair number which can only be addressed by slow deliberate cogitation.

Estimating the materials, labor, and subcontractor costs for a large construction project isn’t a job for intuition. The precise gravitational pull of the moon on a spaceship isn’t something you can learn to recognize to a sufficient decimal place. Auditing your company’s financials should be done deliberately unless you want to feel the whiplash of math to the face.

Which Speed?

Both fast and slow thinking have their place. Both are indispensable. If you had to have pen, paper, a manual, and a calculator to know how and where to throw a baseball, then you wouldn’t win many games. But very few lithium batteries have been designed by intuition.

We try to resolve most of our problems at the level of intuition because it’s faster and easier and only drop into deep contemplation when absolutely necessary. This often creates problems because we begin to develop inaccurate intuitions - we try to solve a slow-thinking problem quickly.

Kahneman gives unending examples of this mismatch. Our fast thinking seeks out narratives and even invents narratives that aren’t there. When our brain finds a story - a cause - then it often ignores everything it knows about statistics and logic. When you hear something growling in the bushes after reading a book about bear attacks, then your brain jumps to conclusions even if the bush is in Central Park and it’s a billion times more likely to be anything other than a bear.

Marketing Fast and Slow

When I read Thinking Fast and Slow years ago it was a revelation to me (I’ve since read it two or three times cover to cover). The model Kahneman provides explains so much about how we perceive and process our way through life. It explains how experts are able to make snap decisions that are sometimes startlingly accurate and how fancy pants Ivy League professors in statistics can be fooled into thinking a character profile works as a librarian even when they know almost no one works as a librarian.

The two-mode model of thinking also explains how people respond to marketing messages and why some messages work and some don’t.

Step One: Math

The most obvious mistake many marketers and entrepreneurs make is to demand that their audience think slowly right off the bat. Many messages for many products (especially highly-technical products) read like a math problem. Even if your audience is technical, these types of messages usually bounce off. It’s not that a VP of Engineering can’t understand what you’re saying, it’s just that she’s not yet decided whether deciphering your message is worth the effort. Her default is to ignore and move on, only diving into deep, laborsome analysis if it feels like it’s worth the time and effort. She has to like the story to be motivated to do the math.

A Face I Don’t Know - And Don’t Want To

The next mistake is to construct a message which is easy to understand but which contradicts something your audience already knows. In this case, the customer’s intuitive response is to be repulsed by the message rather than drawn in - as if your message is an angry, unfamiliar face amid a crowd of faces. If you’re telling me, for instance, that sales teams don’t use enough technology or that your cloud service has more features than AWS, then I probably won’t feel the need to investigate further. My intuition tells me you’re wrong and I don’t feel like thinking hard to test my intuition.

Practically Worthless

The third mistake is for messaging to appeal merely to practicality, “ROI,” “shareholder value,” “30% savings,” or some such businessy outcome. This is, of course, more common with B2B products. I may think the message is plausible - it has the ring of truth - but not really care at a personal level. It is eminently possible for the CFO of a large bank to feel no emotion at the prospect of saving his institution millions of dollars. And unless he cares - unless he feels something when he reads what your product can do for him - he’s unlikely to act. The CFO’s knee-jerk assessment doesn’t provide him sufficient motivation for further action - the analysis, discovery, and calculation necessary to justify your solution. In this case, your audience understands what you’re saying and they aren’t actively repulsed by it, but neither are they drawn in. They just don’t care.

The Rest of the Story

A familiarity with Kahneman’s twofold model enables you to thread your positioning through these errors. It’s a uniquely empathetic understanding of the way people think that can help you meet your audience where they are and bring them where you want them to go.

People think fast and intuitively at first, seeking out narratives that they care about. So go with the flow and conform your opening pitch to how people actually think vs how you want them to think. Say something about your product or company that engages your audience in a narrative they want to take part in. Then once they’ve chosen to be characters in the story, later on you can ask them to slow down and do some math.

Even if you sell ERP middleware, your audience is looking for an intuitive entry point into your product’s capabilities. They’ll do the difficult research and calculations only if you can interest them in a story of how your product is the dwarvish sword which will enable them to slay the dragon of roguish pivot tables, endless deduplication, and missed alerts, leading to the adulation of their fellow townspeople.

Another way of saying this is that your audience has to understand the story, like the story, and see themselves in the story in order to motivate them to hear the rest of the story.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. That’s just one of the dozens of sparkling insights from Thinking Fast and Slow, many of them similarly helpful for those of us trying to communicate ideas. So Rest in Peace Daniel Kahneman. And thanks for helping us to understand each other.