Was Steve Jobs a Techno-Optimist?

Yes...Mostly...But Some Things Just Don't Fit

Steve Jobs was no Luddite.

That much is pretty clear. But does that mean he was a techno-optimist (someone who, as Marc Andreessen puts it, thinks technology is the “good news”)?

Kinda, sorta, probably, yeah. But I’m not so sure. Some things fit, but some don’t.

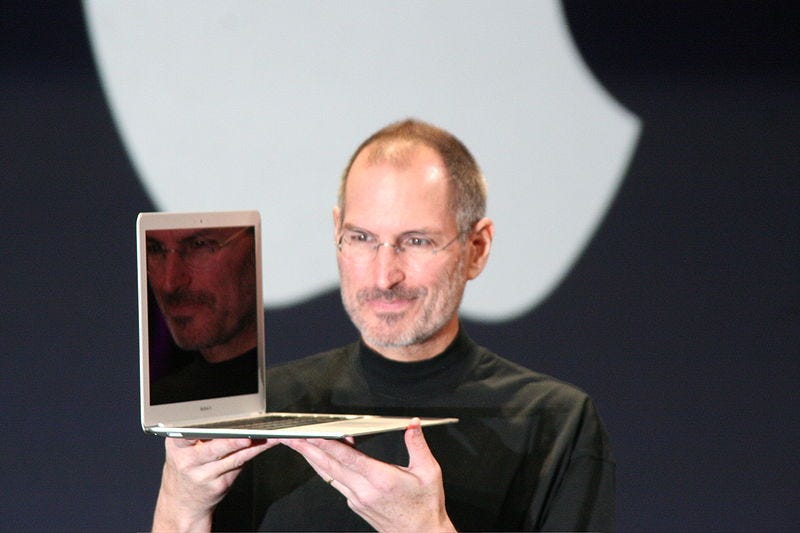

First, the obvious: Jobs was the greatest technology evangelist ever (just stating the facts). It was impossible to experience one of Jobs' keynotes and not to come away a little more optimistic about the present state of technology and what was possible in the future.

I was busy building technology in my first company when Jobs was on his second run at Apple, but when he took the stage, my schedule magically opened up, and I watched the keynote. I (along with the entire tech industry) was in awe. How did he make people so excited about a music player or an OS upgrade? It made you proud to be working in the same industry and on the same kinds of stuff. Every tech CEO at the time wanted to be Steve - and many tried, with results between awkward and comical.

But this electrifying energy and forward momentum that Jobs brought to Apple and to his entire era in tech was tempered by his personal tech-minimalism and the focused perfectionism which he engrained so deeply into Apple’s culture that its influence is only now beginning to wane.

The black mock turtleneck was merely the most distinctive mark of Jobs' austere approach to technology and to life. In his worldview, even the technologies of tables and chairs must not be adopted haphazardly. Jobs famously lived in a nearly unfurnished house for years before marrying Laurene Powell, and even then, according to Laurene:

“We spoke about furniture in theory for eight years…We spent a lot of time asking ourselves, ‘What is the purpose of a sofa?'”

Most people do not take eight years to determine the purpose of a sofa.

Most people have settled that question years ago in a fraction of the time, enabling them to settle their derrieres comfortably into the seat cushion with no further consternation or consideration.

But most people are not Steve Jobs.

Most people buy the washing machine that’s in stock, has good reviews, and fits their budget. But Jobs' own account of this process runs a little differently:

“We spent some time in our family talking about what’s the trade-off we want to make. We ended up talking a lot about design, but also about the values of our family. Did we care most about getting our wash done in an hour versus an hour and a half? Or did we care most about our clothes feeling really soft and lasting longer? Did we care about using a quarter of the water? We spent about two weeks talking about this every night at the dinner table. We’d get around to that old washer-dryer discussion. And the talk was about design.”

Two weeks.

Every night for two weeks!

But that was Jobs, and it’s not all that surprising to hear of his personal obsessiveness because Jobs was like that with everything, especially Apple’s products. He was a purist - relentlessly, brutally focused on creating a few amazing user experiences.

Here’s just a few bits of Steve Jobs lore to illustrate the point:

When Jobs realized inertial scrolling could be used to build a phone, he put delivery of the iPad “on the shelf,” reasoning that even a five billion dollar company with thousands of employees couldn’t launch more than one great product simultaneously.

Jobs drove the same model and color of car for years: a black Porsche 911 (which he would replace every six months). He later exchanged the 911 for a Mercedes SL55S - this time silver. He also owned a BMW Z8, but might have owned dozens more if he could have gotten past the “what is the purpose of a car” question.

On returning to Apple in 1997, Jobs scuttled plans for most of Apple’s products, choosing instead to focus on just 4 computers.

And the $100M yacht that Jobs designed to look like a 250-foot floating iPhone? It took too long to perfect, and he never set foot on board - leaving it to his wife.

Steve didn’t just advocate this approach for himself. He believed others should do more in fewer areas too. No one loved technology more than Steve Jobs, but no one hated mediocre technology more than Jobs. No one felt the same visceral loathing for a menu with too many nested options, a keyboard with the wrong travel, or an unsightly and unnecessary hinge or screw. Among those building technology, no one seemed to care as deeply as Jobs about whether products fulfilled their purpose - whether they created meaning, delight, fulfillment, joy, or connection.

Not just revenue. Microsoft made lots of revenue. Microsoft was an Apple competitor, and maybe that’s explanation enough for Jobs' criticisms of the company to the north…

“I am saddened, not by Microsoft's success - I have no problem with their success. They've earned their success, for the most part. I have a problem with the fact that they just make really third-rate products."

…But it’s hard to escape the fact that Jobs had a point. Somehow success and first-rate products don’t always go together, and this unfortunate combination can leave the world a little poorer even if makes a company a lot richer.

Put another way, Jobs was not an “early adopter” - that so cherished segment of technology buyers - nor a “power user” of most technologies. He didn’t seem to have any desire to clutter up his life or office with barely-functional apps and gadgets for every task and hobby. Try to imagine, for instance, the criteria and process Jobs might have used to decide what devices to carry in his pocket or what went into his carry-on for a trip. Try to imagine what apps were on Steve’s iPhone and the standards they had to meet to get there and stay there: There they are, taking up screen real estate, but what do they do? How do they look? How do they function? Are they simple enough, intuitive enough, elegant enough, delightful enough for a man who lived without furniture rather than buy the wrong table?

Jobs pressed these ideas pretty deeply into Apple. My limited personal experience interacting with the company is that when the industry says “jump,” Apple’s feet stay planted. Apple adopts technology, but it is not haphazardly, indiscriminately, or fast. They are a hard company to sell technology to because they don’t see “cool,” “hot,” and “new” as sufficient criteria for them to adopt, even if their competitors have long since taken the leap. Apple wants its technology systems to create experiences. They spend a lot of time thinking about purpose and design. Doubtless, Jobs taught them that.

That’s why, when I try to place the “techno-optimist” label on Jobs, I don’t think it quite fits - even though it mostly fits. Jobs was overwhelmingly optimistic about technology in aggregate - its role in the forward march of history - but pointedly pessimistic about whether a particular technology was fulfilling the specific human purpose he had for it - whether that was washing cloths, a sitting platform, a glass stairway, or a music player. That’s why Jobs spent most of his life devoted to perfecting a handful of technological categories and why he was not an indiscriminate fanboy of other technologies. Jobs was one of the greatest technologists of all time, but he was also one of technology’s harshest critics.

I think the resolution of this irony is that Jobs understood a few things about technology that most technologists do not:

Human Scale

Up until Jobs' death, the iPhone’s dimensions were restricted by that of the human hand. Jobs wanted to be able to reach his thumb up and touch any part of the screen. Jobs was also an advocate of skeuomorphic design - the practice of making the digital landscape look, and to an extent feel, like objects in the physical world. For the longest time, Apple icons looked like their counterparts in gritty material existence: The Camera looked like a lens, Books were on a wooden shelf, Notes were on lined yellow paper, and even the icons themselves looked like they had physical edges and depth.

Perhaps none of this was necessary. Perhaps the gargantuan screens we carry around today are optimal, and perhaps Jonathan Ive was right to flatten Apple’s design aesthetic. But I tend to think Jobs had a point, even if each implementation of that point could be legitimately debated. For technology to serve us, it has to be scaled to our limitations, shaped around our humanness, and designed to counterbalance our foibles. We can create fighter jets capable of killing their pilots just as we can create apps capable of killing our productivity.

Human Time

In Jobs’ commencement speech in 2005 to Stanford University, he spoke of death as “life’s change agent,” the limiting mechanism by which our energy, passion, and creativity are funnelled into productive use. Without death - without time limits - we might shuffle around in our bathrobes forever, never quite getting around to building anything insanely great. Similarly, all of Jobs’ work at Apple and many of the eccentricities of his private life stemmed from his vivid consciousness of how the limitations of time necessitated focus. Jobs didn’t have time to pick out his shirt in the morning or shop for a different kind of car once he had found a good one, but he had time to create the personal computer and time to design the iPhone.

Then there is the story of Jobs’ own cancer treatment and death at only 56. He opted for a combination of state-of-the-art and alternative treatments (what any one of us might do if we were in his shoes fighting a little-known disease). He didn’t resign himself to death but neither did he appear to pull out all the technological stops and ruin his remaining years of life in a desperate attempt to prolong them.

Human Competence

I indicated earlier that Jobs was not a technology “power user” of most technologies. That statement is incomplete. Jobs was certainly a power user of Apple products and I would suspect Jobs had a high degree of competence with the tech he did choose to use. Most people who use technology every day get good at it. If you work in the technology industry, and especially if you build technology, you can master a lot of different types of technology. After a few years of working 60-hour weeks, even complex technologies can start to seem simple - so simple that you think everyone can and should use them. But even though he spent his entire career in tech, Steve never seemed to lose touch with the fact that for most people, each individual technology is a very small part of their lives, and for it to be a pleasant and fruitful part, it must be kept simple and intuitive.

Jobs saw that adopting too many technology products too quickly is a recipe for incompetence at a personal and organizational level. Better to know and use and build a relative handful of great technologies with complete mastery than hundreds of third-rate ones with ineptitude. And if this was true for Jobs and for Apple, it’s surely true for schoolteachers, carpenters, accountants, and designers. It’s also likely true for you and your company. If you’re a perpetual early adopter of a host of new tech, then you never have time to push a few of those technologies into skillful, everyday use.

Human Purpose

If a computer is, as Jobs said it was, “a bicycle for your mind,” then the most important question is one of destination - of purpose. Steve, more than any technologist of his time (or, for that matter, of our time), was willing to constrain his own and Apple’s technological progress in order to adapt technology to human purposes. If it took eight years of discussing furniture in theory, and if, in the meantime, you had to sit on the floor, then so be it. If it took an extra three years to ensure that the iPad experience was not just a big iPhone, then that was time well spent. If you die before the yacht is completed, then that’s a small price to pay for the ability to focus which only the prospect of death can give you. When it comes to pursuing technological progress, don’t compromise - don’t take shortcuts. If you’re not careful in constraining technology design and clear on its purpose, then it’s likely to lead you somewhere you don’t want to go: to the Zune, not the iPod.

Focusing to Go Faster

The irony, of course, is that even within the severe constraints which Jobs placed on himself and on Apple, he managed to, arguably, advance technology further than any technologist in history. Many of the biggest categories of technological growth are extensions of markets Jobs began or at least shaped.

How was Jobs able to create so much technological progress within such draconian self-imposed limitations? The answer, I think, lies in the fact that Jobs spent orders of magnitude more time than most technologists thinking about the true nature of the human destinations he was seeking to reach: beauty, delight, connection, and creativity. And once he saw the possibility of achieving these ends, he was unwilling to settle. As a result, he took longer to build fewer technologies, but the ones he built were more compatible with the human condition. They felt natural, unintrusive, playful, and elegant. These kinds of technologies have staying power. These kinds of technologies transform industries. Much more so than the constant stream of awkward and often convoluted apps and gadgets we are told we must adopt right now to stay on the cutting edge.

He wasn’t perfect or perfectly consistent. Jobs stumbled into pragmatism from time to time (Antennagate comes to mind), and he was surely motivated by commercial success. But he didn’t want that success to be built on selling junk, and for the most part, he was successful at building commercially viable works of art. Art that fit nicely in the hand and in people’s lives.

The unofficial motto of many technologists and technology consumers seems to echo Zuckerberg’s famous admonition to “move fast and break stuff,” but that was not Jobs' motto. In a way, his whole career was spent fixing user experiences other technologists had broken - whether personal computers, music players, smartphones, or tablets. Sometimes, moving fast and breaking things slows you down in the long run (as perhaps even Meta would now admit), and sometimes, moving slow enough to create technological excellence informed by careful consideration of human purpose is the only way to make real, enduring progress - the kind that doesn’t engender societal backlash and produce as much collateral damage. It took longer for Apple to get to market, but once they got there, the market leaped forward a decade in a day. Apple didn’t enter as many markets, but the ones they entered anchored the entire tech industry.

You may be as optimistic as Jobs was about how technology can move the universe forward. But if you - just you and your company - want to play a part in that progress and put a dent in something as big as the universe, all of your energy has to be directed on a very small surface area. You must be willing to abandon universal progress to make a dent locally. And since life is short and time is fleeting, you might want to first spend some time thinking about dents in theory to make sure you make the right one.